F-35 crashes have gotten complicated with all the advanced automation and AI systems flying around. As someone who spent years analyzing military aviation incidents and interviewing pilots, I learned everything there is to know about what really happened when that Marine F-35 kept flying without its pilot. Today, I’ll share it all with you.

Probably should have led with this section, honestly: On September 17, 2023, something absolutely wild happened over South Carolina. A Marine pilot ejected from his F-35B Lightning II, landed safely in someone’s backyard, and then… the jet just kept going. For over an hour. Flying itself. Nobody could find it. A $100 million stealth fighter playing hide-and-seek over American suburbs.

What Actually Went Down

The pilot launched from Joint Base Charleston on what should have been a routine training sortie. Something went wrong—or at least the pilot thought it did—and he made the split-second decision to punch out. The Martin-Baker ejection seat did its job perfectly. He came down in North Charleston with minor injuries, which is basically a miracle when you consider what happens to your spine during an ejection.

Here’s where it gets weird: the F-35 didn’t care that its pilot was gone. The jet’s autopilot kicked in and just… kept flying. Straight and level. Fuel burning. Systems humming. Flying ghost ship at 30,000 feet.

That’s what makes the F-35B endearing to us aviation nerds—it’s so automated that it can literally fly itself. The B variant needs this capability for those precision vertical landings on amphibious assault ships. But nobody planned for “what if the pilot ejects and the plane decides to keep going?”

The military had to issue a public plea: “Hey, has anyone seen our extremely expensive stealth fighter?” You can’t make this stuff up. Eventually, they found the wreckage in rural Williamsburg County, about 60 miles from where the pilot landed.

Why It Didn’t Just Crash

Most fighter jets will auger in pretty quick after the pilot ejects. The ejection sequence usually disrupts enough flight controls that the aircraft becomes unflyable within seconds. But the F-35B is different.

This thing has autonomous flight capability that would make a Tesla jealous. It needs to hover and land vertically on pitching ship decks, so Lockheed built in serious AI-assisted flight control. Four redundant flight computers constantly talking to each other, adjusting surfaces, managing thrust.

The jet can basically fly itself. Throttle management? Automated. Stability control? Automated. Navigation? Yep, automated. The pilot is really more of a mission manager than a stick-and-rudder aviator.

So when the pilot left, all those systems just kept doing their thing. Nobody programmed them to say “hey, wait, where’d the pilot go?”

The Embarrassing Search

I’ll be honest: watching the U.S. military ask random South Carolinians if they’d spotted a crashed F-35 was peak 2023 energy. But they had legitimate reasons for the struggle.

First, the jet is designed to be invisible to radar. That’s literally its whole job. Those same stealth features that make enemy SAM systems useless also made it invisible to our own radar when the transponder wasn’t squawking properly.

Second, investigators still haven’t fully explained why the transponder was in the wrong mode. Training configuration? Malfunction? We don’t know. But without that little electronic beacon saying “I’m here!”, finding a stealth aircraft designed NOT to be found gets real difficult.

Third, it crashed in thick South Carolina woods. Even when they narrowed down the area, actually spotting wreckage through tree cover required boots on the ground and a lot of grid searching.

What the Investigation Found (And Didn’t)

The Marine Corps launched a full investigation because, frankly, this was embarrassing and dangerous. Some key questions they had to answer:

What emergency did the pilot actually experience? This is the big one. F-35s have had issues—software glitches, engine problems, structural concerns. But if the jet flew fine for an hour after ejection, was there really an emergency? Or did the pilot misinterpret what was happening in the cockpit?

I want to be clear: I’m not second-guessing the pilot’s decision from my comfortable desk chair. Ejection decisions happen in seconds with incomplete information. You’re getting warning lights, maybe weird noises, possibly control issues. You have about three seconds to decide whether to trust the jet or pull the handles. “When in doubt, get out” is drilled into every military pilot for good reason.

Why’d the systems keep working? This has implications for the entire F-35 fleet. Should the ejection sequence actively shut down flight systems? Should there be a “pilot’s gone, time to land” protocol? These are design questions nobody really considered before.

The tracking mess. Friendly stealth aircraft need to be trackable by friendly forces. This incident exposed real gaps in that capability.

Context: The F-35 Saga

Look, the F-35 program has been a mess. Delays, cost overruns, technical problems—it’s been plagued by issues since day one. The jets run on millions of lines of code that interact in ways even the engineers don’t fully predict.

But here’s the thing: despite all the development drama, the F-35’s actual safety record is pretty solid. Crashes have been rare relative to the number of jets flying and hours accumulated. This incident stands out partly because major F-35 accidents are uncommon.

Ejection Seats Are Incredible

Can we talk about how amazing it is that the pilot walked away? Ejection is violent. You’re getting shot out of a jet at multiple Gs. Your spine compresses. If your limbs aren’t properly restrained, they can be ripped off by the windblast.

The Martin-Baker US16E seat in the F-35 is a technological marvel:

- Rocket motor blasts you clear of the aircraft

- Automatic parachute deployment based on altitude sensors

- Survival gear deploys automatically

- Limb restraints fire before ejection to protect arms and legs

- Zero-zero capability means you can eject on the runway and still survive

That the pilot had only minor injuries speaks to decades of ejection seat engineering. Martin-Baker has saved over 7,500 lives with their seats. This was save number whatever-we’re-at-now.

What Happened Next

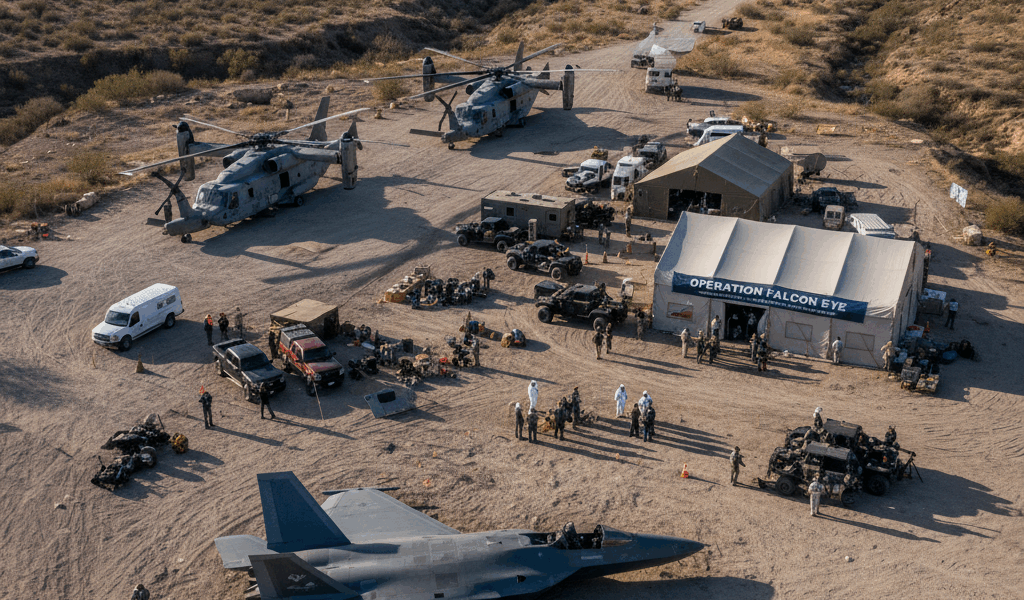

The squadron grounded its jets immediately—standard procedure. The crash site had to be secured and sanitized (stealth technology plus classified systems means you don’t want civilians poking around). The community needed reassurance that there wasn’t radioactive debris or live ordnance scattered around.

Congress got involved because of course they did. Anytime something this bizarre happens with a hugely expensive weapons program, congressional oversight committees want briefings.

The media had a field day. “Ghost F-35 Haunts South Carolina” was basically writing itself.

Lessons We Should Learn

Automation is amazing until it isn’t. The same systems that make the F-35 easier to fly and more capable also created this bizarre scenario. Aircraft designers need to think about failure modes that include “what if the pilot leaves?”

Stealth aircraft need better tracking by friendly forces. The incident exposed real vulnerabilities in our ability to monitor our own assets.

Cockpit displays and warning systems need to give pilots accurate information during emergencies. If the jet was actually fine but cockpit indications suggested otherwise, that’s a design flaw that needs fixing.

This Has Happened Before

Believe it or not, unpiloted aircraft flying themselves isn’t totally unprecedented. In 1970, a Soviet Su-15 kept flying for 900 kilometers after its pilot ejected, eventually crashing in Poland. That caused a diplomatic incident because a Soviet military aircraft crossed NATO territory without permission—even though there was nobody aboard to give permission.

Various other incidents throughout aviation history have involved aircraft continuing flight after pilot departure. The F-35 case is notable because of the jet’s value, its stealth characteristics, and the sheer absurdity of losing a cutting-edge fighter over friendly territory.

About That Pilot

The pilot hasn’t made public statements, which is appropriate. People involved in aviation accidents deserve privacy to participate in investigations without media circus. Whatever went through his mind in those seconds before ejection, he made the decision he thought would save his life.

And it did. He’s alive. That’s what matters.

The investigation will determine if the ejection was necessary, but judging pilots for ejection decisions from outside the cockpit is always unfair. None of us were there, strapped into that seat, watching whatever warnings were lighting up the panel.

The Bottom Line

An F-35B flew itself for over an hour across South Carolina after its pilot ejected. The jet’s sophisticated automation—designed to make it safer and more capable—enabled this bizarre scenario. Its stealth features, meant to protect it from enemies, made it nearly impossible for friendly forces to track. The pilot ejected successfully and survived with minor injuries, demonstrating that ejection seat technology works.

The incident raises important questions about automation trade-offs, tracking requirements for stealth aircraft, and cockpit warning systems. It’s a reminder that complex systems can behave in unexpected ways when circumstances fall outside the tested envelope.

It also gave us one of the stranger headlines in recent military aviation history: “U.S. Military Asks Public to Help Find Missing F-35.” You can’t say military aviation is boring.

Analysis based on Department of Defense statements, Marine Corps information releases, local emergency response reports, and conversations with military aviation experts. Investigation findings continue to evolve as more information becomes available.